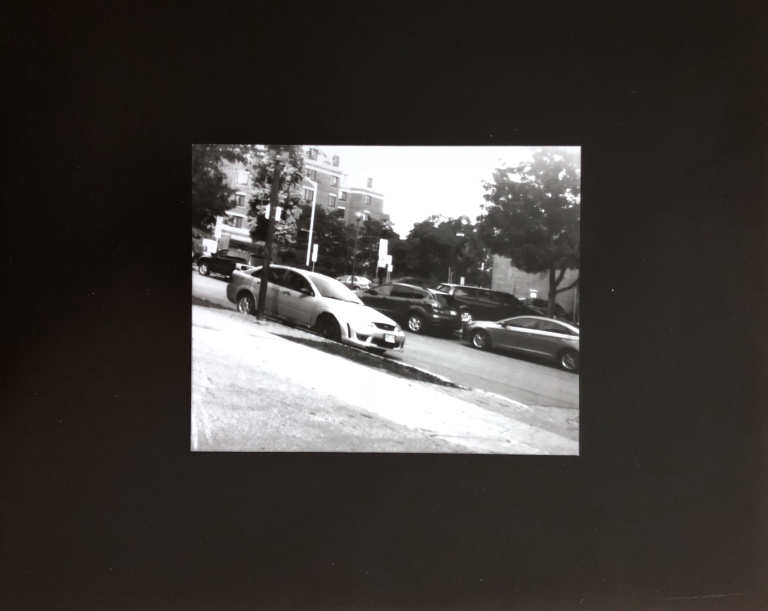

Regular format photography is also known as 35mm photography. The measurement of 35mm references the width of film and can also be found in other sizes. Many cameras that use 35mm film are SLRs, or Single Lens Reflex camera, meaning that there is a pentaprism from the viewfinder to the lens, allowing us to see through the lens. When the shutter is pressed, the mirror will raise and the shutter will activate, taking a photo.

Film is sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light, so you must be cautious when loading and unloading the film from the camera that it is completely wound into the canister. You cannot let the camera see the light until after the fix stage of development. If it is exposed, the film will turn black. Because of this, you have to take the film out of the canister in complete darkness. For this process, see Developing Film.

You have to be aware of the ISO/ASA as this measures the films’ sensitivity to light. If it is sensitive to light, it require less light in exposure. You tell the camera what sensitivity the film is inside the window on the shutter speed measure circle. The lower the ASA, the lower the sensitivity to light, meaning a higher exposure. 400 is normally a good, general purpose film.

Exposure is important in the photo, and you must use the exposure reading by pushing the shutter button half way down. This will show you a plus, green circle or minus as the camera assumes that everything will be middle grey. You want to alter the shutter speed and aperture so you have the green light showing. Ensure you focus before taking the photo. Moving the frame will alter the exposure, meaning you have to change the shutter speed and aperture again.

There is a direct relationship between shutter speed and aperture as when you increase the f-stop, you lower the shutter speed. The give or take, or reciprocity, between the two allows to to roughly gather what settings you may need to change. You shouldn’t shoot anything with a shutter speed longer than 1/60 of a second as it will pick up camera blur.

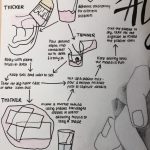

- Shutter speed/TV: smaller number = bigger hole = more light. Bigger number = smaller hole = less light

- Aperture/AV: smaller number = bigger aperture = smaller focus range. Bigger number = smaller aperture = bigger focus range

The consequence of changing aperture is changing the depth of field, or the range that will be in focus. If the aperture is wide open (smaller number), the depth of field will be small. Changing the aperture will re-position the focus of the depth of field and can change the context of the image. You can determine the depth of field with the preview button that is found on the side of the lens. This will determine how much of the image is in focus around the focal point, and will make it seem like the image goes darker.

The depth of field can be changed with aperture along with focal distance of the lens and the camera to subject the distance. The closer the subject to the lens the lower the depth of field (relative distance).

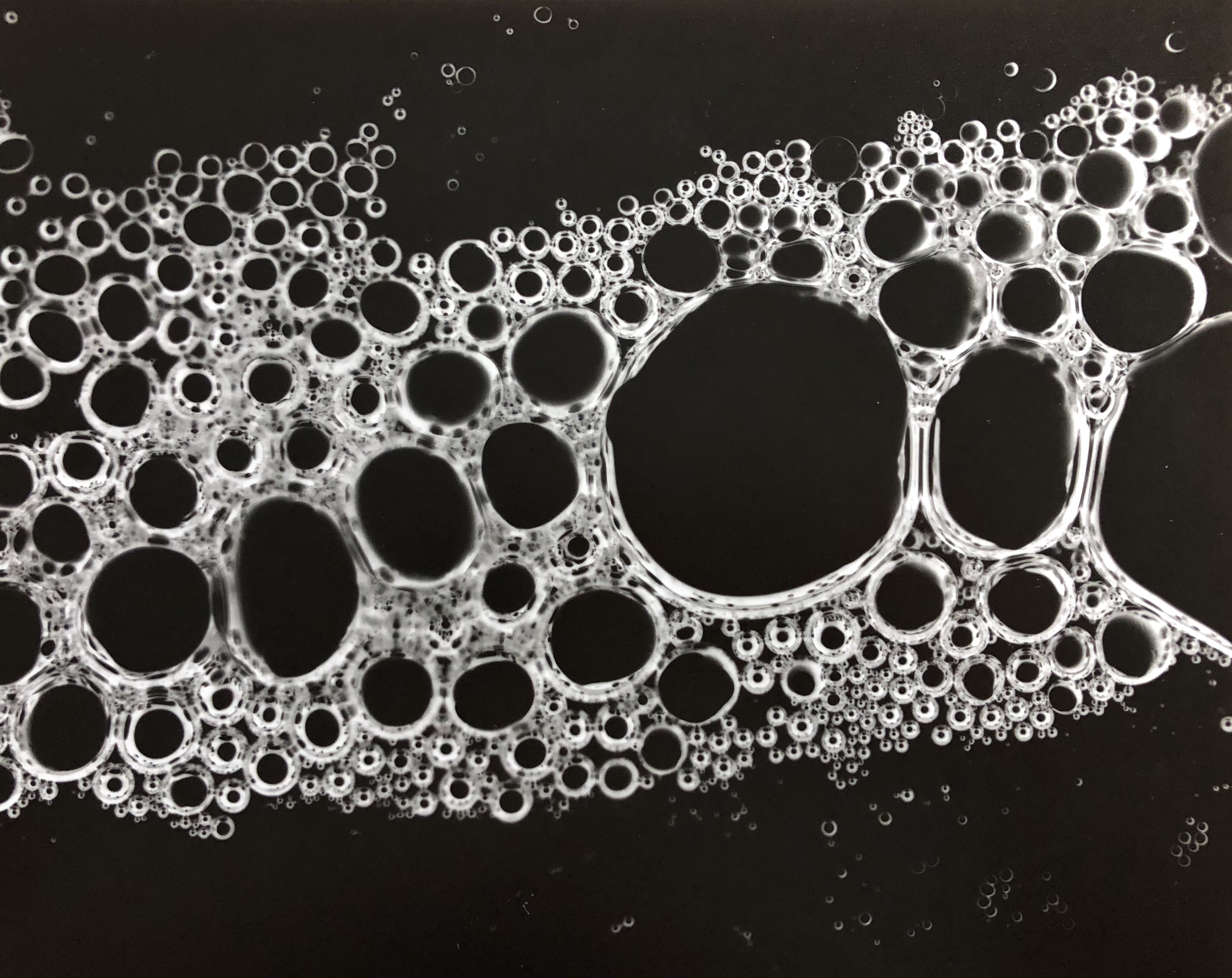

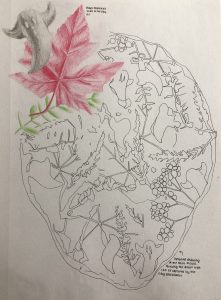

I used all of this theory while using the 35mm cameras to take images for the second photography assignment, Like Nothing You’ve Seen Before.